Supporting Emergent Bilingual Learners Labeled Long-Term English Language Learners (LTELL)

Background Information on Emergent Bilinguals Labeled “LTELL”

Principles to Support Emergent Bilinguals Labeled LTELL

Spotlight on Students: Emergent Bilinguals Labeled LTELL

Supporting Emergent Bilingual Learners Labeled Long-Term English Language Learners (LTELL)

Many young people in U.S. schools receive supports and services under an “ELL” (English Language Learner) designation for extended periods of time – sometimes 7 years or more – without passing their state’s English proficiency exam. When this happens, these emergent bilingual learners (EBLs) are labeled “Long-Term English Language Learners” or “LTELL.” It can be puzzling for teachers to determine how to meet the needs of emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL. This resource is meant to help you understand, educate, and advocate for this population.

The ideas and examples we will share in this resource draw on the expertise and years of experience of the CUNY-NYSIEB support team, whose members have guided dozens of schools across New York State to develop best practices for emergent bilinguals, including those labeled LTELL. We draw on our core principles in all the work we do, which view bilingualism as a resource in education and support a multilingual ecology for the whole school.

Before we start, a quick note about language: If you are new to CUNY-NYSIEB’s work, you may be wondering why we refer to students as we do. Labeling so often characterizes emergent bilinguals’ learning experiences in school: they are called ELLs (English Language Learners) or LEPs (Limited English Proficient), terms that emphasize what they can’t do or don’t have. We refer to these students as Emergent Bilingual Learners (EBLs) to emphasize their skills (bilingualism) and their growth potential (emergence).

I. Background Information on Emergent Bilinguals Labeled “LTELL”

How do we get to know emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL?

A helpful place to start is clarifying which students in our schools are identified as Long Term English Language Learners (LTELL). Essentially, if a student has been receiving ENL (English as a New Language, also called ESL) services for multiple years (the exact number of years differ from state to state) without passing the state’s English proficiency test, he or she can be assigned this label. All students labeled LTELL are in middle or high school.

It is also important to note that most students with this designation speak English very fluently. They have been in the U.S. for years, many from birth, and their oral English skills are strong when used socially. Emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL typically use both English and their home language(s) with family members, friends, and in their communities.

Despite these linguistic strengths, emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL often score below grade level in school-based literacy tasks or assessments that are administered in English or in their home language (Olsen, 2010). Yet we must be careful not to generalize these students’ knowledge and abilities based on scores on assessments. Emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL may still be in the process of acquiring language and literacy skills for academic purposes in English as well as in their home language, but they are still capable of highly complex and dynamic bilingual language practices (Ascenzi-Moreno, Kleyn, & Menken, 2013).

Along with recognizing and leveraging students’ abilities and resources, educators should keep in mind the many factors that may contribute to the school performance of the diverse population of emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL. Without attention to these factors, these students are at high risk for dropping out of high school before graduation and not going on to college.

Characteristics of emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL in terms of prior schooling and language practices: Research by Menken, Kleyn, and Chae (2012) identifies three main groups of emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL:

- Students who have received inconsistent U.S. schooling: Students in this category have been shifted by their school system between bilingual education, English as a second language (ESL) programs, and mainstream classrooms with no ‘ESL services.’

- Transnational students: These are students who have moved back and forth between the United States and their families’ countries of origin during their school-aged years and may or may not have gaps in their schooling history.

- Students who have received monolingual language support: Some students receive ENL programming consistently, but these programs have failed to build upon the students’ home language practices thus limiting their progress in English development.

For more on identifying and supporting emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL, check out this comprehensive resource from the National Education Association (NEA):

For more on identifying and supporting emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL, check out this comprehensive resource from the National Education Association (NEA):

What can schools do for emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL?

Emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL still need ENL services, even though they have been in the U.S. schooling system for many years. What schools must do is ensure these students have consistency in programs and services. Additionally, viewing these students’ home languages as a resource allows teachers to strategically build on students’ bilingualism in instruction. As a teacher, it is also important that you understand that the needs of emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL are different from those of emergent bilinguals with other designations. Designing programs and interventions with this specific population in mind can be critical to their success.

CUNY-NYSIEB has designed a Framework for the Education of ‘Long Term English Learners’ which details different programmatic, curricular, pedagogical, and classroom structures for best meeting the needs of emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL. It is available for download here:

CUNY-NYSIEB has designed a Framework for the Education of ‘Long Term English Learners’ which details different programmatic, curricular, pedagogical, and classroom structures for best meeting the needs of emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL. It is available for download here:

II. Using CUNY-NYSIEB Principles to Support Emergent Bilinguals Labeled LTELL

In our experience working with schools, a few strategies have stood out as particularly promising for emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL. We highlight classroom examples from CUNY-NYSIEB cohort schools where these strategies have been successfully implemented. We present them here divided into “school-based” and “classroom-based” practices, to differentiate between what we have seen successfully implemented on a schoolwide level and what individual teachers have accomplished with these students.

Effective programs for emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL help students build on and extend their strong communicative oral language base (in both English and the home language) in ways that support their development of the language and literacy necessary for academic purposes.

A. Supporting Emergent Bilinguals Labeled LTELL on a Schoolwide Level

School-Based Practices

1. Use multiple sources of data to drive instruction

Scores on standardized English language proficiency tests can help teachers group students, differentiate, and drive instruction. At the same time, given the diverse experiences and knowledge of these students, teachers should use other sources of data as well, including student oral presentations and commentary, student writing, reflections, and performance tasks.

CUNY-NYSIEB Successful Strategies: Using Multiple sources of Data to Drive Instruction Emergent bilinguals are designated LTELL often because they fail to pass one test – a State English proficiency exam – for many years in a row. Research urges that certain types of assessments, like a State proficiency exam, can lead to “deficit” while others can lead to “promise” (Mahoney, 2017). Particularly with vulnerable populations like emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL it is crucial to assess their abilities and plan accordingly, using a variety of methods that lead to “promise.” Some ideas include:

- Students view a rubric and ask questions about it prior to a writing assignment

- Students make an oral presentation on a topic, in addition to a writing assignment

- Teacher uses a checklist to gauge students’ oral language production during group work

- Teacher uses results of a reading retell, role play, and standardized reading assessment to make decisions about what level the student should advance to

For more ideas like this, please see past CUNY-NYSIEB Associate Investigator Kate Mahoney’s book The Assessment of Emergent Bilinguals

2. Rigorous Home Language Arts geared towards emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL

It is very important that emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL receive explicit instruction in their home language. Home Language Arts (HLA) classes build on and extend the strong oral communicative skills these students bring to school. HLA classes are not the same as world language classes, but rather teach home language literacy skills.

CUNY-NYSIEB Successful Strategies: HLA for Emergent Bilinguals Labeled LTELL At one cohort high school, CUNY-NYSIEB team members recommended to the administration that they create a focused bilingual language and literacy block for their students designated LTELL. This language and literacy block included an English as a New Language (ENL) class, an English Language Arts (ELA) class, and an Home Language Arts (HLA) class. They decided to work with students whose home language was Spanish because of the school’s resources – bilingual teachers and Spanish as a foreign language teachers. In the first year of its initiation, the teachers of these classes worked with the school’s ENL lead teacher and CUNY-NYSIEB support staff to plan collaboratively in order to align broad topics of study and the literacy skills that are taught. One example of a project they completed that year was a study of ceramics done in collaboration with an area museum the school had partnered with. Students read and wrote about the artistic genre in both literacy classes (ELA and HLA) and in ENL had supplemental vocabulary instruction and opportunities to practice content area vocabulary in multiple contexts (presentations, discussion, role play). The teachers also worked to highlight cognates wherever possible, to boost the connections students were making between languages. They also collaborated with the art teacher on their own project. As a culminating celebration, families were invited in and students were able to present their artistic work and academic learning in both English and the home language. The following year, students that had benefited from this bilingual literacy and language block were able to participate in a high level Spanish course and at the course’s end scored well enough on the culminating exam that they received college credit in foreign languages. Successful uses of translanguaging strategies in the ELA/HLA block include:

- Connections to home language and families (unit celebration)

- Explicit vocabulary instruction highlighting connections between home language and English

- Cross-curricular connections with explicit focus on language instruction

- Multiple opportunities to use home language and practice new language

3. All teachers are language and literacy teachers

Emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL make great progress when math, science, and social studies teachers, in addition to ENL, ELA, and HLA teachers, develop language and literacy objectives that support their content objectives (Ascenzi-Moreno, Kleyn & Menken, 2013). This necessarily will include the home at strategic moments, such as when reading, taking notes, and speaking aloud to partners in their home languages in order to access content and develop their language and literacy skills (García, Johnson, & Seltzer, 2017).

4. A school team that meets regularly to describe and review the education of emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL in the school and individual students’ progress

Emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL make great progress when math, science, and social studies teachers, in addition to ENL, ELA, and HLA teachers, develop language and literacy objectives that support their content objectives (Ascenzi-Moreno, Kleyn & Menken, 2013). This necessarily will include the home language at strategic moments, such as when reading, taking notes, and speaking aloud to partners in their home languages in order to access content and develop their language and literacy skills (García, Johnson, & Seltzer, 2017).

CUNY-NYSIEB Successful Strategies: Emergent Bilingual Leadership Team At all of our cohort schools, we worked with educators and administration to form an “Emergent Bilingual Leadership Team.” This was a group of educators interested in learning more about programs, practices, and supports for emergent bilingual students. Many of these teams met to discuss ways to support emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL. If you are interested in learning more about starting an group like this in your school, please visit Establishing Your School’s Emergent Bilingual Leadership Team, where you will find helpful presentations, a professional development guide, and a resource packet (image linked on the right).

B. Supporting Emergent Bilinguals Labeled LTELL at the Classroom Level:

1. Encourage student independence with cooperative learning and partner work:

Emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL benefit from strategies that encourage them to become independent learners. They can work in collaborative groups with students more proficient in English, and also serve as resources for other students/each other. They can also learn to become independent and reflective learners. This requires teachers to be strategic in the way they group students and approach instruction, as described in continuation:

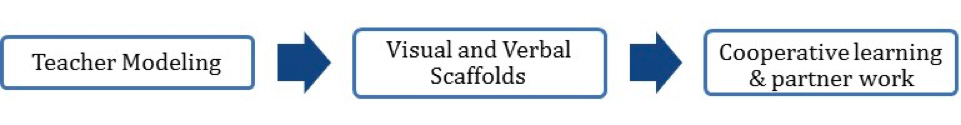

CUNY-NYSIEB Successful Strategies: Gradual Release of Responsibility A key structure we have encouraged teachers to use with emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL is the gradual release of responsibility model of instruction (see Figure 1), which begins with teacher modeling and visual and verbal scaffolds and continues toward student independence with cooperative learning and partner work (Freeman & Freeman, 2011; Frey & Fisher, 2009; Gottlieb, 2006). Figure 1. Gradual release of responsibility model of instruction A review of research suggests the following pedagogical structures are the most helpful for teaching academic concepts and vocabulary using a gradual release of responsibility:

- Teacher modeling is effective when it is interactive, allowing for student feedback, and when students understand both what to do and how to do it;

- Guided discussions help students get ideas from classmates and review key concepts;

- Group work is only effective when students work together effectively with each one making contributions; and

- Partner work and independent work are only effective when students are prepared and understand a task

2. Build spaces for students to create and reflect upon goals

Emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL know they need to “work hard,” but may be unclear on exactly what that entails. Teachers and advisors can help students select and set goals for reading, writing, language, speaking, and behavior, and then reflect on them at set intervals. Teachers can also model behaviors that help them meet goals, like effective study skills.

CUNY-NYSIEB Successful Strategies: Creating and Reflecting on Goals Modifying the way they approached portfolios helped one cohort middle school encourage their emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL to be more reflective learners. In a blended ENL/ELA 7th grade class, the co-teachers worked with CUNY-NYSIEB support staff to create multilingual “reflection sheets” students used in conjunction with their class portfolios to write reflections on their work. These reflections had a specific language focus: in addition to using a rubric to reflect on what they had improved on and what they need to continue working at for each portfolio piece, students also looked at ways in which they had made progress in English (vocabulary, language structures, word choice, etc.). Prior to writing about their goals, students also shared work with peers and discussed it in any language to clarify their ideas. Successful uses of translanguaging strategies to integrate literacy into content include:

- Reflection chart is multilingual

- Explicit focus on language structures

- Multilingual partner work

3. Embed opportunities for structured oral language development

While emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL have strong communicative oral language, they need opportunities to develop academic oral language. This, in turn, can also help develop academic written language. Some example activities include presentations, debates, theater activities (including role play), and discussions. Language and content goals should be planned into these lessons.

CUNY-NYSIEB Successful Strategies: Structured Oral Language Development In the CUNY-NYSIEB guide A Translanguaging Pedagogy for Writing, a writing unit is described that embeds many targeted opportunities for oral language development. In this unit, which has students write “best of” neighborhood reviews, students are encouraged to use oral language to interview community members, create short videos, make oral presentations, and work in collaboration with other students. There is also an explicit focus on making connections between home language and English. For more information, you can download the guide below; the unit described here is called “Middle and high school sample unit: ‘Best of’ neighborhood reviews” and begins on page 97.

4. Provide curricular materials that are connected to students’ backgrounds, interests, and reading levels in English

Classroom materials that build on the backgrounds and interests of emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL will engage students, promote deeper levels of understanding, and increase comprehension of content (Ebe, 2015). These resources should include technology and allow students to meet the required standards while at the same time be relevant to emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL. Particularly for older students who have not yet achieved grade-level proficiency in English, a way to get them engaged in literacy is through high-interest texts that are also highly readable.

| CUNY-NYSIEB Successful Strategies: High interest, relevant, and readable books |

| The resources highlighted here are book sellers or series that in some cases are also available in other languages, and that deal with themes young people identified as LTELL can relate to:

The Bluford Series is a collection of young adult novels written in a highly readable style. Set in contemporary urban America, they deal with issues relevant to the lives of today’s students. Orca Book Publishers is a Canadian children’s book publishing company that features many “hi-lo” series (high interest, low reading level) for young adults, and specialize in books that represent people of different ethnicities, abilities, and those who identify as LGBTQ. Lee and Low Books is the largest multicultural children’s bookseller in the U.S. Their multi- genre “Tu Books” collection is high-interest and targets diverse middle/high school readers. |

5. Pay attention to vocabulary and language structures

Emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL need support to develop the kind of language schools expect them to use in the content areas. When explaining the result of a scientific experiment, for instance, students not only need to learn specific science vocabulary words, they also need the language to explain what they observe by employing causal expressions such as: as a result, for these reasons, or consequently. Planning language and content objectives for lessons in all subject areas allows teachers to attend to the development of academic language LTELL students need to be successful (Freeman & Freeman, 2009).

| CUNY-NYSIEB Successful Strategies: Focus on Vocabulary and Language Structures |

| The co-teaching model for ENL push-in services was successfully used in one cohort high school to encourage teaching language and literacy in all content areas. Working in collaboration with the ENL push-in teacher, CUNY-NYSIEB support staff helped design lessons that would highlight vocabulary and language structures. In one science class where many LTELL students were present, for instance, the students were studying reaction time and how it relates to the central nervous system. The ENL teacher previewed the vocabulary for the lesson, connecting it to students’ prior knowledge and home languages. She also previewed the materials for the lesson, using physical examples and highlighting action words (verbs). Then, the science teacher provided the content instruction about a lab they were going to do that day, while the ENL teacher supported students in small groups. During the lesson, both teachers supported the students as they worked in English and the home language to comprehend and complete the lab. Subsequently, the ENL teacher modeled how to write the lab report using the past tense.

Successful uses of translanguaging strategies to integrate literacy into content include:

|

Spotlight on Students: Emergent Bilinguals Labeled LTELL

As you will see, each of the students described here have unique stories. They have received different services from their school and from their teachers and have different learning needs, preferences, and personalities. These profiles serve as an example of the vast diversity of emergent bilingual students labeled LTELL. It is very important that educators learn about how unique each of their students really are, regardless of the labels that they have received.

Rupjit, 14, 8th Grade Student from Bangladesh

Rupjit is a 14-year old originally from Bangladesh who arrived to the U.S. in 2nd grade. He has been receiving different types of ENL services consecutively since he arrived. Currently in 8th grade, his school now provides him pull-out ENL services.

Rupjit speaks both English and Bengali very fluently, though he often uses short, simple sentences when he speaks English. While he does not speak Bengali in class, he often speaks it during lunchtime and transition times with his peers. With his peers, he is playful and talkative. He is always the first in line to hold the door for the class during transitions.

With reading, Rupjit struggles to decode words in both English and Bengali. The keys to capturing his interest in learning are the two C’s—computers and cricket. In addition, his teachers often modify texts with pictures and have given him articles on cricket translated into Bengali. While this helped Rupjit to be more engaged in reading, he still demonstrated little comprehension of the texts. He is working to strengthen his ability to recognize letter-sound correspondence. While Rupjit has produced little writing in English, he has written some sentences in Bengali; however, his teacher does not speak Bengali, and there are no educators at the school who are able to decode his writing.

Rupjit loves science and enjoys conducting experiments. In English class, he works best when he reads using technology. During independent reading time, he completes selections on an online digital library called MyON, and on a leveled reading and math program called I-Ready. Unlike some other students who prefer one-on-one support, Rupjit prefers to work either independently using technology or in small homogenous groups. Overall, he responds well to small group intervention, computer technology, and audio books.

Javier, 17, 11th Grade Student from the U.S.

Javier is a 17-year old student born in the U.S. of Panamanian descent. He has been receiving ENL services since he entered school in kindergarten (11 consecutive years). Javier also has a specific learning disability, so he receives additional learning services under an Individualized Education Plan (IEP). He is in 11th grade and in his different subject classes he receives instruction through an integrated co-teaching approach, where two or more teachers provide general education, special education, and/or ENL support to students.

Javier loves cooking and would like to study to be a chef when he graduates. He also loves to draw. He is social, polite, and gets along well with his peers. Javier speaks both English and Spanish at home. While he has strong Spanish literacy skills, Javier still prefers to speak and write in English. He demonstrates strong comprehension of written texts and the ability to retell or paraphrase what he has read. In addition, he is a talented creative writer who enjoys crafting imaginative narratives and poetry. Overall, Javier struggles with organization and applying appropriate mechanics in his writing. He is inconsistent with distinguishing claims from counterclaims and using transitions to connect body paragraphs with claims. Also, he often has challenges remaining on task.

Successful strategies that Javier’s teachers have tried include given him question prompts, using graphic organizers, applying annotation routines, and providing redirection. When they give him prompting with questions, most of the times Javier can recognize and implement corrections on his own. For organization, one of his teacher notes that T charts have helped Javier organize his ideas for an essay when she provided a pre-filled organizer for him to insert relevant information. This teacher also notes that teaching him an annotation routine has helped Javier improve reading comprehension. He is now able to apply these routines without prompting, and this has helped his reading comprehension and writing.

Eduardo, 16, 11th Grade Student from the Dominican Republic

Eduardo is a 16-year old who arrived from the Dominican Republic in 4th grade. He has been receiving ENL services for eight consecutive years, in different formats; for example, he has been in a few bilingual Spanish-English classes, as well as ENL services in various formats (pull-out, push-in). In 11th grade now, Eduardo’s ENL services are provided by his general education teacher who is also ENL certified.

Eduardo speaks Spanish at home. However, when he first started high school, he did not want to be placed in bilingual classes. His oral and written skills in Spanish were at grade level, but he did not want to do school work in Spanish. Now in 11th grade, Eduardo has had a change of heart and started to value his bilingualism. He is now a tutor, helping younger students in Spanish. During his study halls, he works with a small group of boys and tries to be a role model for them. Eduardo is also an artist who produces music and writes the lyrics for his songs in Spanish. He loves writing, reading Spanish and English literature, and History.

By the time he started high school, Eduardo was very comfortable speaking in English but he needed to work on his writing skills, in particular in grammar. He was very motivated during his freshman year, but 10th grade was very hard for him. He began challenging authority figures and refusing to do his work. This year, however, he realized that being disrespectful to the teachers would affect his future and so changed his attitude. His writing has developed during the year. He responds very well to specific feedback in order to revise his work and he takes the time to edit and make changes to improve his writing. By the end of 11th grade, he is very motivated to go to college and has done very well on his end of the year exams in English. While he struggled in math, particularly on word problems, he has also improved in this subject and has passed his Algebra final exam.

Want more? Here are some Helpful Links:

- A Framework for the Education of ‘Long-Term English Learners’: 6-12 Grades: A CUNY-NYSIEB guide that provides programmatic, curricular, classroom, and pedagogical strategies and resources aimed at best meeting the needs of emergent bilingual students labeled LTELL.

- CUNY-NYSIEB Framework for Students with Low Home Literacy: A CUNY-NYSIEB guide that consists of a set of six recommendations on educating emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL and SIFE that can be adapted with flexibility to meet the specific needs and strengths of the students, the educators, and the school.

- Colorín Colorado’s Long-Term ELLs: A small database of materials including videos, articles, and booklists for further information on emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL.

- Meeting the Unique Needs of Long Term English Language Learners: An NEA publication that describes seven basic principles for meeting the needs of emergent bilinguals identified as LTELL.

- Writing Screener: Available in English and 9 languages commonly spoken by emergent bilinguals labeled LTELL, this tool provides a quick way to assess students’ basic writing skills in their home language.

Additional Resources and Works Cited:

Ascenzi-Moreno, L., Kleyn, T., & Menken, K. (2013). A CUNY-NYSIEB Framework for the Education of ‘Long-Term English Learners’: 6–12 Grades. New York, NY: CUNY-NYSIEB, The Graduate Center, The City University of New York. Retrieved from http://www.cuny-nysieb.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/CUNY-NYSIEB-Framework-for-LTELs-Spring-2013-FINAL.pdf

Celic, C., & Seltzer, K. (2012). Translanguaging: A CUNY-NYSIEB guide for educators. New York: CUNY-NYSIEB, The Graduate Center, City University of New York. Retrieved from http://www.cuny-nysieb.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Translanguaging-Guide-March-2013.pdf

Ebe, A. (2015). The power of culturally relevant texts: What teachers learn about their emergent bilingual students. In Y.S. Freeman & D.E. Freeman (Eds.), Research on preparing inservice teachers to work effectively with emergent bilinguals. Bingley, UK: Emerald Books, Ltd.

Freeman, D., & Freeman, Y. (2009). Academic language for English language learners and struggling readers: How to help students succeed across content areas. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Freeman, D., & Freeman, Y. (2011). Between worlds: Access to second language acquisition (3rd edition). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Frey, N. & Fisher, D. (2009). The release of learning. Principal Leadership, 9(9), 18–22.

García, O., Johnson, S.I., & Seltzer, K. (2017). The translanguaging classroom: Leveraging student bilingualism for learning. Philadelphia: Caslon.

Gottlieb, M. (2006). Assessing English language learners: Bridges from language proficiency to academic achievement. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Mahoney, D. K. (2017). The Assessment of Emergent Bilinguals: Supporting English Language Learners (1st edition). Multilingual Matters.

Menken, K., Kleyn, T. & Chae, N. (2012, August). Spotlight on ‘long-term English language learners’: Characteristics and prior schooling experiences of an invisible population. International Multilingual Research Journal, 6(2), 121–142.

Olsen, L. (2010). Reparable harm: Fulfilling the unkept promise of educational opportunity for California’s long term English learners. Long Beach, CA: Californians Together.

Acknowledgments

This CUNY-NYSIEB resource was created by Kathryn Fangsrud Carpenter, Ivana Espinet, and Elizabeth Pratt. Maite Sánchez and Kate Seltzer served as advisors to the authors. We would like to give special thanks to the teachers and administrators who provided feedback on this resource.